Technology Survey: A Sampling of Counter-UAS Systems – JED, May 2019

– By John Knowles and Hope Swedeen –

The market for counter-UAS systems, also known as counter-drone systems, is not even 10 years old, but it has seen explosive growth across military, government and civilian applications. The drones they are designed to detect and defeat are often small, inexpensive and simple to operate. Their payload is typically a camera providing real-time, full motion video that is data-linked back to the operator. But some users have weaponized these drones, as well, which makes them higher-priority threats. These drones are everywhere, and this market factor, more than any other, is driving the strong demand for counter-UAS systems.

Drones are heavily dependent on accessing the Electromagnetic Spectrum (EMS). They use the EMS for the command link from the operator to the drone, for the camera sensor, for the datalink from the drone back to the operator, and sometimes for GPS/GNSS-based navigation. As a result, drones are vulnerable to passive RF detection, identification and tracking, as well as RF jamming and EO/IR jamming. Thus, many counter-UAS systems employ electronic attack subsystems as part of their countermeasures suites.he market for counter-UAS systems, also known as counter-drone systems, is not even 10 years old, but it has seen explosive growth across military, government and civilian applications. The drones they are designed to detect and defeat are often small, inexpensive and simple to operate. Their payload is typically a camera providing real-time, full motion video that is data-linked back to the operator. But some users have weaponized these drones, as well, which makes them higher-priority threats. These drones are everywhere, and this market factor, more than any other, is driving the strong demand for counter-UAS systems.

Over the past several years, the user base has become more sophisticated about defining requirements. A Brigade Combat Team, for example, may have a need for a deployable counter-UAS system that can detect and engage multiple drones at longer ranges, and it may be primarily interested in quickly damaging or destroying the drone(s). On the other hand, a requirement to protect a government facility may emphasize multiple sensors integrated with a command and control system and countermeasures that are more automated (to minimize the man-power needed to operate the system). The counter-UAS system may also be integrated with other facility security systems. In another example, a counter-UAS system that is protecting a public event typically needs to be deployable, perhaps operate at shorter ranges and employ non-kinetic countermeasures that enable security personnel to take control of a drone’s command link and to safely land it away from crowds.

With such an evolving variety of users and requirements, industry has responded with a wider range of counter-UAS solutions. Some are as simple as a hand-pointed, high-gain directional antenna connected to a backpack-mounted control unit and battery. This type of system relies on the operator’s eyes and ears as sensors and is typically designed for short-range engagements. Others are more sophisticated, with multiple sensors, such as radar, EO/IR and ESM systems, a command and control system and multiple types of kinetic and non-kinetic countermeasures.

Comparing this month’s survey to JED’s first Counter-UAS Survey in September 2017, one continuing trend is companies offering a range of counter-UAS solutions, with each one suited to different sets of customer requirements. The industry’s use of teaming and partnerships also remains strong, as new players emerge with partial solutions that are competitive either in terms of price or performance.

A few of the larger defense electronics companies are beginning to commit more resources to counter-UAS opportunities, especially for programs with unique military requirements. A few of them are reflected in this survey, but most of these companies are working under development contracts from the DOD to adapt high-energy laser (HEL) or high-power microwave (HPM) technologies to meet counter-UAS requirements.

This month’s survey differs slightly from the previous counter-UAS survey (from September 2017) in that we included systems that only provide ESM and DF detection and tracking systems. (Our previous survey only included systems that provided an integrated countermeasures solution.) Most of these “detection and tracking-only” types of systems interface with multiple third-party countermeasures solutions. Several new companies are listed, as well, which reflects how rapidly the market is growing.

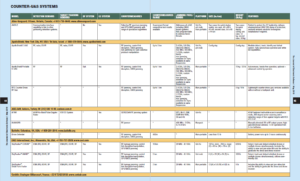

THE SURVEY

In the survey table, the first column lists the model name. Working from left to right, the next two columns cover the sensors used to detect and track the drones. (In the case of manpack “drone guns,” the detection and tracking columns are empty because the “sensors” are usually the human operator.) The next column indicates if the system provides a direction finding (DF) capability, which is useful in locating the drone as well as the drone operator. The next column indicates if the counter-UAS system features a command and control capability with a workstation or other type of user interface. The next few columns cover the system’s countermeasures performance characteristics, such as techniques, range and operating frequencies. The remaining columns list configuration, size and weight. ♦

Click here to view the complete survey table. For the best viewing experience, open in PDF viewer and select “Two Page View” in Page Display settings.

If you enjoyed this article, please share. If you would like to read more articles like this one, we encourage you to join the AOC to receive a copy of JED every month.